Feed for Thought: Feed Usage in Aquaculture

written by Corinne Noufi

Feature photo courtesy of American Unagi

Feed for thought while grocery shopping

The increase in human population will increase animal protein production and overall environmental impact

The human population is increasing, food demand is rising, and all of this is impacting the environment. In 2016 global meat production reached 318 million tons.24 At the rate we’re currently headed, animal production is projected to increase 45% by the year 2050, which means we will need to produce upwards of a staggering 460 million tons of animal protein.11 Further, the environmental impact of producing that tonnage will depend on which type of animal protein we eat, as raising different animals requires different resources. And of course, alongside this projected 45% increase in demand for animal protein will be a corresponding increase in the need for animal feed production, because of course… our food needs to eat too!

Farmed seafood is positioned to increase in production alongside livestock and poultry

What’s a consumer to do in order to make a well-informed decision while grocery shopping? Considering a primary contributor toward the overall environmental impact of raising animals for human consumption is the production of their feed, this article takes a deeper dive into specifically feed issues – in particular, farmed fish feed in comparison with other animal feed such as livestock or poultry. After all, seafood is now widely pointed to for being a healthy and environmentally conscious substitution for the meat-dominant diet of the western world,2 28 and as wild capture fisheries stabilize, it will be an increase in farmed seafood production that will keep up with the growing population.

Three main points of interest regarding farmed fish feed production

We’ve identified three major points of interest when considering farmed fish feed which we discuss further below:

- Farmed fish are way more efficient at converting their feed, meaning it takes less feed to produce a pound of food for us than most of the land animals we eat.12 13 20

- In reality the vast majority of wild fish harvested for non-human consumption goes into land animal feed, not farmed fish feed.9 15 So choosing not to eat farmed fish does not diminish the pressure on wild fish stocks. Further, the wild fish stocks that are harvested for non-human consumption shouldn’t be automatically assumed to be overfished or poorly regulated.

- Farmed fish don’t necessarily require wild fish-based diets. Herbivorous farmed fish, such as tilapia or catfish, need a different nutrition profile altogether, and carnivorous farmed fish, such as rainbow trout and kampachi (amberjack or yellowtail), are increasingly being fed alternative diets without wild fish with successful results.4 5 16 19

Point 1: Understanding feed efficiency

Feed efficiency is important for raising animals and we talk about it with a ratio

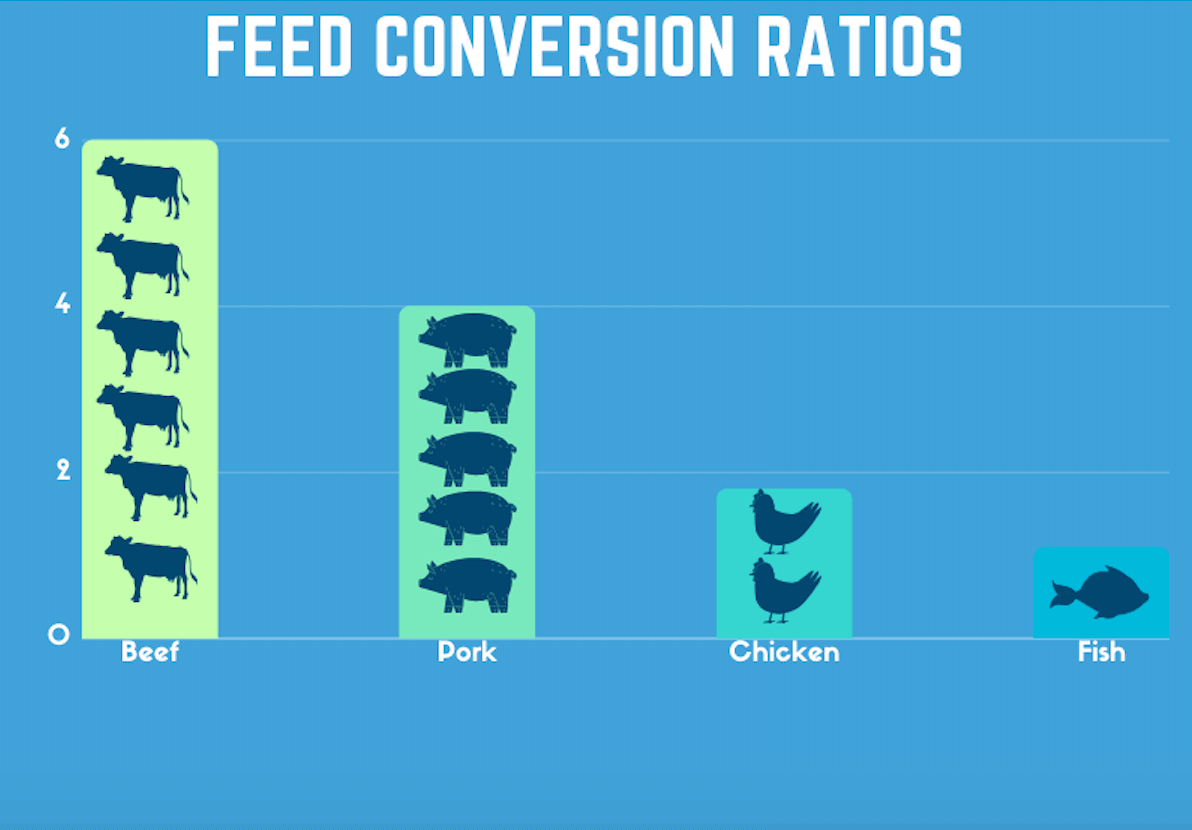

Beginning with the seemingly obvious, whether terrestrial or aquatic, all farmed animals are raised on feed. However, less obvious is that livestock and aquatic animals differ in the efficiency of how they metabolize feed, that is, convert it into the meat, dairy, or eggs that we eat. Farmers use a feed conversion ratio (FCR) to track how efficiently different animals grow. This ratio will depend on a variety of factors, but essentially, the lower the ratio, the less feed it takes to make our food.

Shopping Tip: Look for animal protein choices with low feed conversion ratios.

Farmed fish are more efficient at converting their feed than land animals

Global Aquaculture Alliance. (n.d.).Beef has an average FCR of 6, meaning it takes 6 lbs of feed to produce 1 lb of beef.25 Pork and chicken average at 4.0 and 1.8 respectively, while the average for farm-raised finfish clocks in at only 1.1 (note farmed shellfish is less than 1.0 because as filter feeders they do not require any feed).13 26 This means it takes only around 1 lb of feed to produce 1 lb of fish meat for humans. While already notably lower than livestock, feed conversion ratios for aquaculture are expected to further decrease as continual innovations in feed technology arise, which we discuss below. For now, our major point is to highlight that animals with lower feed conversion ratios are converted into human food that has used less resources, thereby contributing a lower impact on the environment.

Global Aquaculture Alliance. (n.d.).Beef has an average FCR of 6, meaning it takes 6 lbs of feed to produce 1 lb of beef.25 Pork and chicken average at 4.0 and 1.8 respectively, while the average for farm-raised finfish clocks in at only 1.1 (note farmed shellfish is less than 1.0 because as filter feeders they do not require any feed).13 26 This means it takes only around 1 lb of feed to produce 1 lb of fish meat for humans. While already notably lower than livestock, feed conversion ratios for aquaculture are expected to further decrease as continual innovations in feed technology arise, which we discuss below. For now, our major point is to highlight that animals with lower feed conversion ratios are converted into human food that has used less resources, thereby contributing a lower impact on the environment.

Farmed fish need a lot less feed than livestock

Another factor when considering animal feed efficiency is just how much feed is required to raise the animals we eat. When comparing the total tonnage used across the whole animal feed supply chain, a whopping 93% goes to livestock. Of the other 7%, the entire pet food industry, including horses (a 25 billion dollar a year industry in the US alone), accounts for 3% of that total animal feed, leaving a mere 4% used by aquaculture; a sliver in comparison to livestock.1 In fact, 150 million tons of feed is produced on an annual basis exclusively for livestock, whereas only 1.8 million tons of feed is produced for aquaculture as of 2015.1 That’s 80 times more reliance on land, water, and fertilizers to produce livestock than if we, as consumers, were to seek out and choose a responsible source of farmed fish. Alltech. (2015)

Alltech. (2015)

Point 2: Understanding wild fish harvested for farmed fish feed

But wait, aren’t wild fish used to feed farmed fish, and isn’t that counterproductive? That would be counterproductive…but consider the following:

Livestock requires most of the wild fish captured for animal feeds, not aquaculture

Wild fish are used to make animal feed not only for farmed fish but for livestock as well. The most recent report from the FAO in 2016 shows that of over 90 million tons of wild fish harvested, 19.7 million tons were used for non-human consumption, which we recall from above is mostly animal feed.8 Much of this feed was undoubtedly used to produce livestock feed, as we saw above where livestock requires 80 times more feed than aquaculture.

It requires roughly only a quarter kg of wild fish to produce one kg of farmed fish

Over the last decade, the ratio of wild fish required to produce 1 kilogram of farmed fish decreased from 0.63kg to 0.22kg.10 So farmed fish require less than one wild fish, arguably stretching the value of nutrition that one wild fish would have provided. Fish in: Fish Out (FIFO) ratios for the conversion of wild feed to farmed fish, including salmon. (n.d.)

Fish in: Fish Out (FIFO) ratios for the conversion of wild feed to farmed fish, including salmon. (n.d.)

The wild fish stocks harvested for animal feed aren’t necessarily overfished

The vast majority of wild fish used to formulate fish feed comes from small fish species like anchovies whose stocks have been shown to be more resilient to fishing pressure than previously thought.14 These anchovy and sardine fisheries also have historically had a very low consumer demand (except for the occasional pizza topping or Caesar dressing ingredient). Further, to automatically assume that the wild fisheries harvested for animal feed production are probably all overfished would be false. According to Dr. Ray Hilborn, renowned global fisheries biologist, "83% of small pelagic fishes (the kind of fish used as feed in aquaculture) are not overfished. Fisheries management has significantly advanced since peak exploitation in the 1980s and wild fisheries no longer carry the doomsday stigma. Of much more concern should be overall environmental impacts from animal food sources." Find Dr. Hilborn's in depth explanation of over and under fishing among the world’s fisheries here.

30% of the “wild fish” component in all animal feeds are the scraps from humans

Scraps from fish processed for human consumption actually make up a significant 30% of fish meal or fish oil used in feeds.17 Why waste nutritious heads, cartilage, and meaty bits from fish caught for humans to eat that won’t be utilized directly by us? This is not to dodge the fact that some wild fisheries are certainly harvested with the sole purpose of supplying animal feed supply chains, and this includes aquaculture. But the reality is that we humans rely on a lot of different animal resources to sustain ourselves, and unfortunately it doesn’t often feel like it’s done in a thoughtful or transparent way. All the above factors taken together provide us with at least some fuller context in how we utilize wild fish stocks as animal feed, both in aquaculture and livestock.

Clean Tech, & Sworder, C. (2017)

Clean Tech, & Sworder, C. (2017)

Point 3: Farmed fish are being fed alternatives to wild fish

Utilizing less wild fish in farmed fish feed

Recall that farmed fish more efficiently convert their feed into human food than livestock. This efficiency is only expected to improve due largely to the quality of protein used to formulate fish feed. Over the past fifteen years, feed formulation companies have been improving their aquaculture feed blends in order to provide farmed fish an appropriate diet that minimizes waste.7 Since 2000, farmed fish diets have decreased in their ratio of wild fish used in feed formulas by 40%.9

Insect protein alternatives to wild fishmeal for farmed fish feed

New alternatives to using wild fish in fish feed are on the horizon.6 16 For example, a group of scientists in the Netherlands have developed a fish feed made of black soldier flies. After four years of testing, they were able to raise fish just as quick and tasty as before.3 23 This means today’s (and tomorrow’s) farmed fish will have increasingly less reliance on wild fish for the same nutrients.

Soy protein alternatives to wild fishmeal for farmed fish feed

While the thought of using soy is counterintuitive to what we associate as a biologically appropriate diet for farmed fish, scientists have demonstrated that fishmeal actually isn’t necessary for healthy fish growth, even in species traditionally reliant on fish.5 Soybeans are a surprisingly promising protein alternative in feed, producing less food waste than feed formulated from wild fish or livestock byproduct and have a comprehensive amino acid profile beneficial to fish health.29

Soy protein can be nutritionally appropriate for farmed fish feed and produce delicious fish

Soybean farmers have begun teaming up with fish farmers to provide high quality fish feed to farms around the US. Researchers from the US Department of Agricultural Research Services have now demonstrated rainbow trout can grow successfully in Idaho on a 100% soy-based diet.21 Not only did soy-raised trout grow just as well as trout raised on a 100% fishmeal diet, a 2017 French study showed that consumers detected no difference during blind taste tests.22 To reiterate, French consumers, who tend to take their food seriously, detected no difference. Similarly, scientists from University of North Carolina Wilmington have used plant-based alternatives in case studies for black sea bass.18 27 Black sea bass is normally reliant on feeds from wild fish, specifically menhaden, for proper growth and nutrition. However, scientists replaced up to 70% of the menhaden fish meal with soybean meal resulting in similar health and growth to fish raised without soybeans.

While soy is a monocultured crop with many drawbacks of its own, we can at least feel better equipped to make decisions knowing now that fish consume less of these types of potentially problematic crops and converts them more efficiently into food for us. Specifically seeking responsible examples of today’s farmed fish allows us to decrease our reliance on the quantity of crops usually devoted to livestock.

Algae alternatives to wild fishmeal for farmed fish feed

Today’s farmed fish is also moving toward reducing or replacing wild fish meal by exploring algae as a nutrition alternative. Ocean Era, an aquaculture research company based in Kona, has been working with support from NOAA and USDA researchers to experiment with replacing fish meal and fish oil with algae and agriculture byproducts on kampachi, or amberjack, feeds.19 The results from early trials have shown that kampachi not only survive but thrive on a diet with zero fish meal. Says Neil Sims, founder of Ocean Era, “We want to see feed companies incorporate these results and further develop the commercialization of their formulas. We want our research to have direct applications in the real world, to soften humanity’s footprint on the seas, and to change the way that the world views seafood.” Neil’s company has been granted a further $3.7 million dollars to continue developing offshore algae culture systems as an alternative fish feed solution. To learn more about his company's R&D projects, read our interview with Neil here.

Herbivorous farmed fish have never needed wild, or any, fish in their feed

Plants, yeast, algae, and insects all contain the necessary amino acids and fats to supply most dietary needs of many farmed fish species.17 18 It’s worth noting the above examples of promising case studies only describe carnivorous fish. Let’s keep in mind species that are not carnivorous, such as tilapia or catfish (for more examples visit this article), don’t require any fish in their diets, meaning they are already raised on feed completely free of fish. Explore this table highlighting different approaches and the innovative direction the aquaculture industry is headed in order to soften its overall environmental footprint of farmed fish feed production.

Can eating responsibly farmed fish help build a path to sustainable food production?

Because we eat animals and animals need to eat, all forms of animal feed production inevitably have some level of impact on the environment. Yet today’s aquaculture uses less feed than livestock, and it continues to improve with efforts to reduce these impacts. Further, while feed conversion ratios for livestock have remained fairly constant, efficient feed usage for aquaculture has made tremendous strides and continues to do so. As Halley Froehlich, Assistant Professor at UCSB and co-leader of Conservation Aquaculture Research Team, reminds us,

"While there is uncertainty around the exact quantity and composition of human diets in 2050, seafood will inevitably be a part of it and could play a larger role if diets shift – something which has the potential to improve human and environmental health. If the US wants to continue to play a significant role in future sustainable seafood production, aquaculture needs to be part of that discussion both domestically and pertaining to trade implications."

Whether the higher conversion efficiency, simply less feed needed, or advancements in wild fish replacement, we as consumers can begin to feel better informed about considering responsible sources of farmed fish among our dietary shifts today and into the future.

SOURCES

1.Alltech. (2015). 2015 Global Feed Survey 2015 | ALLTECH GLOBAL FEED.

2.Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJ, Smith P, Haines A. The Impacts of Dietary Change on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Land Use, Water Use, and Health: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165797. Published 2016 Nov 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165797

3.Belghit, I., Liland, N. S., Gjesdal, P., Biancarosa, I., Menchetti, E., Li, Y., … Lock, E.-J. (2019). Black soldier fly larvae meal can replace fish meal in diets of sea-water phase Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquaculture, 503, 609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.12.032

4.Brinker, Alexander, and Reinhard Reiter. “Fish Meal Replacement by Plant Protein Substitution and Guar Gum Addition in Trout Feed, Part I: Effects on Feed Utilization and Fish Quality.” Aquaculture, vol. 310, no. 3-4, 2011, pp. 350–360., doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.09.041.

5.Callet, T., Médale, F., Larroquet, L., Surget, A., Aguirre, P., Kerneis, T., Labbé, L., Quillet, E., Geurden, I., Skiba-Cassy, S., & Dupont-Nivet, M. (2017). Successful selection of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) on their ability to grow with a diet completely devoid of fishmeal and fish oil, and correlated changes in nutritional traits. PloS one, 12(10), e0186705. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186705

6.Cho, Renee, et al. “Making Fish Farming More Sustainable.” State of the Planet, 25 Apr. 2019, blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2016/04/13/making-fish-farming-more-sustainable/.

7.Clean Tech, & Sworder, C. (2017, December 7). Feeding Fish to Fish: How Insect Farming Fixes Fishmeal. Retrieved from https://www.cleantech.com/feeding-fish-to-fish-how-insect-farming-fixes-fishmeal/

8.FAO. (n.d.). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5555e.pdf

9.FAO. (n.d.). SOFIA 2018 - State of Fisheries and Aquaculture in the world 2018. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/state-of-fisheries-aquaculture

10.Fish in: Fish Out (FIFO) ratios for the conversion of wild feed to farmed fish, including salmon. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.iffo.net/fish-fish-out-fifo-ratios-conversion-wild-feed.

11.Froehlich, H. E., Runge, C. A., Gentry, R. R., Gaines, S. D., & Halpern, B. S. (2018). Comparative terrestrial feed and land use of an aquaculture-dominant world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(20), 5295–5300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801692115

12.Fry, J. P., Mailloux, N. A., Love, D. C., Milli, M. C., & Cao, L. (2018). Feed conversion efficiency in aquaculture: do we measure it correctly? Environmental Research Letters, 13(2), 024017. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaa273

13.Global Aquaculture Alliance. (n.d.). Why It Matters " Global Aquaculture Alliance. Retrieved from https://www.aquaculturealliance.org/what-we-do/why-it-matters/

14.Hilborn, R., & Szuwalski, C. S. (2015). Environment drives forage fish productivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(26). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507990112

15.Hoffner, E. (2012, May 12). Farm animals consume 17 percent of wild-caught fish. Retrieved from https://grist.org/article/fish-and-pigs-and-chickens-oh-my/

16.Naylor, R. L., Hardy, R. W., Bureau, D. P., Chiu, A., Elliott, M., Farrell, A. P., … Nichols, P. D. (2009). Feeding aquaculture in an era of finite resources. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(36), 15103–15110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905235106

17.NOAA. (2018, April 6). Feeds for Aquaculture. Retrieved from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/insight/feeds-aquaculture

18.NOAA. (2018, February 6). The Future of Aquafeeds. Retrieved from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/aquaculture/future-aquafeeds

19.“Projects.” Kampachi Farms, ocean-era.com/projects.

20.GSI Protein Production Facts. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://globalsalmoninitiative.org/en/sustainability-report/protein-production-facts/#energy-retention.

21.Roberts, T. (n.d.). Examining a New Kind of Trout. Retrieved from https://www.uidaho.edu/research/news/research-reports/2016/food/trout

22.Rickertsen, K., Alfnes, F., Combris, P., Enderli, G., Issanchou, S., & Shogren, J. F. (2017). French Consumers’ Attitudes and Preferences toward Wild and Farmed Fish. Marine Resource Economics, 32(1), 59–81. doi: 10.1086/689202

23.Souvant, Guillaume, and David Doubilet. “Why Salmon Eating Insects Instead of Fish Is Better for Environment.” Farmed Salmon Can Eat Insect Feed Instead of Controversial Fish Meal, 5 Feb. 2018, www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/02/salmon-insect-feed-fish-meal-netherlands/.

24.Shahbandeh, M. (2019, October 28). Meat production worldwide, 2016-2018. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/237644/global-meat-production-since-1990/

25.Shike, D. (n.d.). Beef Cattle Feed Efficiency . Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20160616072736/http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1027&context=driftlessconference

26.Stender, D. (n.d.). Swine Feed Efficiency: Influence of Market Weight. Iowa State University. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20150909053400/http://www.swinefeedefficiency.com/factsheets/IPIC25h SFE Influence of Market Weight.pdf

27.Sullivan, K. B. (n.d.). Replacement of Fishmeal By Alternative Protein Sources in Diet for Juvenile Black Sea Bass. University of North Carolina Wilmington. Retrieved from https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncw/f/sullivank2008-1.pdf

28.Tilman D, Clark M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature. 2014;515(7528):518‐522. doi:10.1038/nature13959

29.Using Soy to Feed Fish. (2019, November 7). Retrieved from https://ussoy.org/about-aquaculture/using-soy-to-feed-fish/.